Poems of resistance - Writing poetry about frustrations, hope, and standing up against the system3/15/2023 A poem ain't gonna change the world. But learning how to create and be comfortable doing it will. Change does not come by repeating what was, but by birthing something new. Creation is a god-like act. It does not just happen. Life is busy, tiring, pressuring. It takes time and energy to carve into our schedule space for creativity. To foster this feeling, to nurture it, so it can nurture us in return and pour over other dimensions of our life and back into the world. Avoiding the social reproduction of the world requires also standing up against inertia, the masses, structural constrains. It requires some level of Courage. There is always some level of risk involved for those willing to put their head above the water to push for social change. Courage to stand up on our own against what is and what needs to change does not happen in a day. We need to learn how to be navigate our fear, work with it, keep pushing in spite of it. Standing in front of a crowd, in public, reading a poem we have created, for many is something out of our comfort zone. Pushing against our fear, one public display of creativity at a time, helps us grow in confidence. Standing on our own, yet not really alone. To curate a space and structure some time for our students to put these ideas into practice, Alex Stoffel and I organised a poetry activity on Thursday 16 2023 as one of the teach-outs taking place at the London School of Economics during the 2023 strikes over pensions and pay This is how we introduced the activity to the students: "We thought this would be a wonderful opportunity to reconnect and spend some time together outside of the regular setting. The objective is to share our frustrations and hopes for the higher education system. Everyone is invited to come (please don't hesitate to invite others!) and should bring along either poetry you have created or that others have written. The poetry doesn't have to be directly about academia; it can be related to any themes of resistance and creating a different future, individually or collectively." The activity was completely voluntary. To help students prepare themselves and give them a boost of confidence, we organised a get-together a few days before. The event was a blast. As one of the participants shared on Twitter, it was truly a "magical" experience. Yes, we did drop "some nasty rhymes" but it was also about putting ourselves out there, standing up together and inspiring each other. As another of the participants shared after the event: "Overall, it was simply one of the best things .... to be part of something much bigger than our everyday, mundane life :)" Because this is not something many of us had done before and in the context of the global classroom, where many of our students face pressure regarding censorship from their home country, VISA and scholarship status, we aimed for the activity to be as inclusive as possible. We shared the following with the students prior to the event:

- Alex, I and the students who volunteer can read the poems of the students who want to write poems anonymously; - I invite all students who have written poems to send them to me after the event so I can publish them as a blog post on my methodological artist blog. Those who want will be able to publish them anonymously; - Some students suggested coming up with masks/hats to avoid facial recognition. This would be visually very powerful, especially if a group of you do it. Please don’t feel pressured to do it, but if some of you want to organise a masked intervention you are very much welcome. - Whether or not you write poems, you are always welcome to join the teach-out on Thursday 16 as part of the audience." As one of the students who contributed to the event anonymously commented: "Showing solidarity with academics during the strike actions in such creative forms is memorable. I find the teach-outs and marches very politically awakening. As an international student, it's a precious opportunity to learn how the higher education system works and how the flawed mechanism can affect academics and students. Having been living in an authoritarian context before coming to study in the UK, I haven't had any chance to join a march and protest for myself and make an appeal. I cherish expressing solidarity with you all." Below are the poems of the students who volunteered to share them on the blog-post. Some of the poems come with a bit of context (at the end of the poem) that the students wanted to share with us, for example when the poem is centred around a specific reference to LSE or their experience. I hope you'll enjoy reading the poems and participating in this creative journey as much as we did 😍 In the teaching pot of the crazy weird witchBy Audrey Alejandro, the Methodological Artist Here is the video of me reciting the poem the day of the event. Thank you Pilar Elizalde for the recording. Once upon a time in a land far way In the wild I was born. Through the earth, through the air, Through the shadows, through the sea Life and work got me here, in the intellectual concrete Some call L.S.E. Hired I became. Cooking for my students Prepar-ing for them my wee-kly potion: 1 Litre of analytical wit to sharpen the mind 1 cup of courage to help grow a strong spine 1 spoon of unknown for the imagination A few words of magic for the transformation How sweet is the taste of the witchy witch poison. I’m cooking, I’m cooking … but something‘s going on. Do you hear anything? Let me pay attention. A mutter in the sky, a murmur in my heart. I hear a word: despair. Where is it coming from? Thousands of admin files laced in regulations. They shriek. Neo-liberal eyes, red and dull, modern abomination. They speak: “Her ideas are quite weird She doesn’t brush her hair. She wears too much colour. She won’t go anywhere.” Witch-hunters in disguise. They come. They try to hunt me down. But what did I expect? I signed my name in the book of the beast after all, didn’t I? Dehumanisation monster, factory for the mind, All that for my pay-check. Life undead, depletion, exhaustion spells. Where can I go for help? I look inside. Sekhmet, Hecate, Chhinnamasta, Cerridwen. Goddess of wisdom and change. We call upon you, I the crazy weird witch and the children of the new. Give us courage. Give us strength. Show us the path and guide us through. Silence. Then the goddess softly says: “Rise poets. Rise. Rise from these dreadful ashes. I bless a reform for this institution. Consume none. Provoke many. Rise into the brave inspiring adults you were always meant to be.” Beaver the Believer, Leave her? You Deceiver! By Miyuki Shiraki Beaver the weaver See her build and burrow Strong-willed and thorough Thrilled to claim space As if there’s no tomorrow Meagre branches See her She dances Bring the twig Tease her She advances Mapping margins Stacking in the gardens Hard work pays off Believe her She’s Beaver the believer Then In the Eden Where the beaver is eager Time stops A sudden seizure Crime stomps On her future The beaver feels weaker Annoyed and devoid With a void deployed Delusional is the institutional Imputable, not excusable Today, a long wait The days elongate It’s like an endless hike This current strike Casualisation, pay gaps, and withdrawing from Stonewall Deceiver, can’t you see her? Why leave her? Keep her, Beaver the believer “To know the causes of things” You know what dramas that bring, Deceiver, you leave her Beaver and the teacher Teach her, the creature, Beaver the believer To be the achiever Context: The beaver is LSE mascot. The poem uses the beaver as a metaphor to express what it feels like to be a willing and hardworking students in the current system. Remould It Nearer to the Hearts Desire by Walter Schutjens And the men who hold high places Must be the ones who start To mould a new reality Closer to the heart But now high places have high salaries And thus think themselves apart These high places are these glass towers That grow further from the heart LSE's founders forged into much older stained glass And thus, unto us impart A demand for social justice through knowledge Made directly from the heart Knowledge derived from knowing the cause of things our motto: Rerum cognoscere causas if you're smart Knowledge of real working conditions Using both our heads and heart To move away from this progressive political legacy And let neoliberal technocrats freely play their corruptive part Would mean losing our direction and humanity The substance of the heart Their casual casualization of effective education Will force future generations to restart In their slow progress to freer societies That lie nearer to the heart This management is an affront to LSE's history And yet they seem to make it into their art To laissez fairly undermine its very foundation And drive stakes through this beaver’s heart Context: This fact may strike people as unlikely nowadays, but it is no coincidence that the same people who founded the Labour Society were also the founders of our LSE. These people were the Fabians and they inscribed in its very motto the critical dictum that it retains today: rerum cognoscere causas 'know the cause of things', this dictum is in its nature progressive at it promotes understanding of society by its roots, much like the method of the reformist socialist project they initiated in the early 20th century. In the back of the Shaw Library on the 6th floor of the Old Building one can find a stained glass window that was made on the day of LSE's opening, at the top of this modern interpretation of classical liturgy one finds the biblical dictum: 'Remould It Nearer to the Hearts Desire' - it captured the socialist social scientific project LSE was to embark on; but what has come of it when a modern LSE doesnt respect the basic workers rights of its employees. This poem is a reflection on LSE's heritage and what has changed. The first stanza is lent from the classic Rush song: 'Closer to the Heart'. I stand aloneby Gabby Unipan I stand alone In a foreign country Far from friends, family, and home Am I alone? I feel so far away I find myself waiting, watching, yearning For an unrecognizable reality, a home, a school, a society I have never known. I stand alone Grieving an experience I could have had, Should have had. Stolen out of my grasp By an invisible, seemingly invincible, divisible force We all recognize but fail to kill It smothers us, blinds us, Snuffs out our senses This force, this system Robs our autonomy Reduces individuality to marketability I stand alone, Forcibly deprioritizing the things I value most Community, connection, creativity In favor of my profitable qualities I stand alone, screaming into the void, Counteracting the commodification of my experience, Of my labor, Of my learning, Of my teachers, My classmates, my friends, my family, My creativity. Do you stand alone? Will you stand with me? How Can It Be by Ruth Boardman How can it be that the very institutions given the power to educate, Those who want to learn and strive for a better future, Those who aim to better not only themselves but future generations, Those aiming to create a safer and more respectful culture. How can it be that those very same institutions publish research on equality, Civil, social, economic, health, political. Research that is used in different sectors of industry, Leading to outcomes that twenty years ago would have been thought of as miracles. How can it be that these very same institutions who cite values of integrity and diversity; Claiming to build sustainable futures for people alike, Leave their staff fearing for their jobs, Causing them to strike. How can it be that these very same institutions whose research leads to miracles, Has a third of academic staff on temporary contracts who are hourly paid, These are the academics facing job insecurity, Unsure if they’ll be returning to work or facing the blade. How can it be that these very same institutions who seek to drive positive change, Have decided to accept a negative change in its staff’s pensions, With a guaranteed loss in retirement incomes. Are you not aware of this condescension? How can it be that these very same institutions preaching diversity, See ethnic, gender and disability pay gaps. Ironically publishing papers on gaps in other industries, Whilst falling themselves dangerously into the trap. How can it be that these very same institutions, Who myself, my friends and those who study here, Have paid thousands of pounds to learn from your academic staff, Are suffering due to your inability to make these inequalities disappear? How can it be that these very same institutions, Are failing their staff and students? Maybe Someone Hears Usby Hongli Liu Maybe we can be excellent in teaching, But we lack the energy. Maybe we always show up in class, But we lose the passion. Maybe we work endlessly to get job done, But our time and work are not respected. Maybe we understand education systems change, But we never thought our situation would be on the margin. Maybe we want to give our best to students, But our real-life situation drains us. Maybe … we are all fragile human beings, But we have been treated like superheroes. Maybe we just want to show our resistance via strike, But nobody listens. Or, If anybody is listening... So, we look up, where does our help come from? Does it come from those who sit in these tall buildings? No, our help comes from those who listen and acts upon our words. Context: "We" – refers to the people who love teaching and are passionate about working in academia. This is something that I have heard and felt through the concerns of many lovely people working in academia, not only here, but also around the world. How they expressed the difficulties and struggles they face to being an academic. This is not a poem that tries to speak for people!! It’s simply to show some love and support, and my hope is that these words could resonate within our heart 😀 You say, I seeby Macquarie You say the rainbow ugly, I see we shining in your dictionary; You say we deviant and silly, I see we writing down your obituary. Dancing coord, Singing pulse; Unnamed color, Unbuttoned coat; You say we are nothing, I see we are everything. I see you watching, I see you listening; Stop raping my mother tongue, Stop murdering my sisters young. “The Child is father of the Man,” But all you do is wear your masks deadpan; Dude, we are making it real, We shall bear no child to be our Achilles’ Heel; We are the last generation, We’ll shout that out loud on your coronation. Your voice is unequivocal, My tears are political; Because in love I see all the possibilities, In love, I see all the divinities. I see les feuilles tombent en dansant, Le soleil se couche en éteignant, Le cœur se brise en saignant, Le cheval rouge court en suant, La mer déferle en rugissant, La chanson finissant en continuant, Le petit prince part en disant adieu tendrement. Context: This poem is about being young and lgbtq in a country where being lgbtq means living in fear and constantly under pressure. On a rainy picketby Alex Stoffel

My first day on a picket line, It was cold and rainy. A bus honked in passing, And a friend said to me, “Solidarity feels like you’re turning inside out.” We spoke about teaching, but about marking and metrics, and a bus honked in passing. We spoke about research, but about submissions and citations. while another bus honked. Three more years on the picket, It’s cold and rainy. We speak about academic struggles, about holding them, like prized possessions, turning inwards on ourselves. My fourth year on the picket, the bus drivers have won their dispute. We speak about winning, about turning outwards into politics. We smile in anticipation, As a bus honks in passing. It’s cold and rainy, but I say to my friend, “Solidarity turns you inside out.”

0 Comments

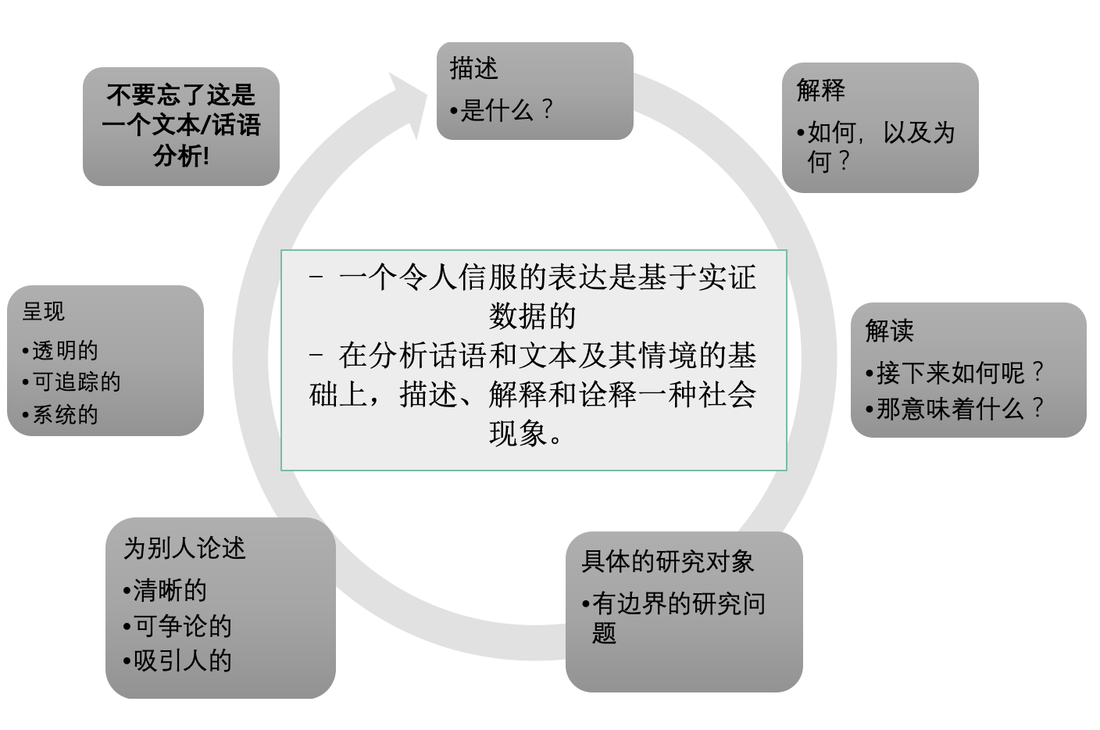

如果作为学生,你曾被告知:你的研究“描述性太强”,你需要“更具分析性”; 如果作为一名教师,你曾告诉你的学生:你们的作业“描述性太强”,缺乏“分析深度”。 那么,你应该来读读这篇文章。  seriykotik1970-房间里的大象 seriykotik1970-房间里的大象 事实上,尽管我们普遍鼓励让作业和研究论文“更具分析性”,但老师可能从未让学生知道,什么是好的分析标准。分析,可以说是社会科学殿堂中的一头大象,包括所有的那些带有“数据分析”字眼的相关课程——例如我所开设的“话语分析”。 那么,什么是分析,以及要怎样才能实现良好的分析工作? 什么是分析?分析是一个转化的过程:原始数据和信息本身并不具有意义,是我们通过分析的过程赋予其意义。 分析也是一个创造的过程:我们通过分析所创造的是,关于世界的新话语,它帮助人们以不同的方式感知世界,从而理解他们在阅读我们的研究之前,不知道或不理解的事情。 但分析是如何生效的呢?分析又是如何使世界变得有意义的呢?笼统地说:分析,通过聚焦、整理、命名以及建立范式与关系,来帮助其他人建立对这些范式与关系的感知,从而以不同方式理解世界。 有一个关于分析的比喻很好,那就是天文学家和其他观星爱好者识别星座的工作。天空布满了星星,但是尽管如此,有些人还是在天空中画出了图案,给这些图案命名,甚至围绕着这样形成的形状创造了一系列故事。这种感知天空的方式代代相传,被人们传授并写在书上,了解过这些知识的人在看星星的时候,都会不自觉地注意到星座。 以下,是来自方法论专著中的两个关于分析的定义: “从字面上看,分析是将复杂的东西‘分解’成较小的部分,并以这些较小的部分的属性和它们之间的关系,来解释整体” (Robson 2011: 412) “分析是给数据带来秩序的过程,它将已存在的东西组织成模式、类别和描述性单元,并寻找它们之间的关系;‘解读(interpretation)’涉及在分析中赋予意义和重要性,从而解释模式、类别和关系...”(Brewer 2000: 105) 这些定义,突出了分析工作中的双重过程。一方面,分析工作是对复杂混乱的现象进行分解和简化;另一方面,分析工作会在选定的元素之间建立模式,以产生一种解释世界的新的混合思路。 在研究的实际操作中,一个小时的访谈,转录记录可能会多达40页纸,而10个访谈的转录记录,就相当于400页纸。我们需要将我们的材料分解成可管理的部分,并专注于某些元素而放弃其他元素,以便我们能识别出隐藏在这些数据中的最有趣的知识。 这是否意味着万事俱备? 作为社会科学家,从我们的数据中创造任何意义和话语是可以的吗?我说过,分析是一个创造性的过程,但这是否意味着可以创造一切? 答案当然是否定的。意义不是原始数据所固有的,而是研究者在培育经验材料的过程中,与其共谋的结果;因此,这一观点并不意味着从社会科学的目的出发,我们能从数据中随意创造任何话语。 针对我们需要怎么做才能实现良好的分析的问题,我们需要制定一些明确的标准,才能帮助我们确保我们的分析目标处于正轨。总结一下就是说:分析的目的是在基于经验数据的基础上,产生一个令人信服的证明,以描述、解释和解读一个社会现象 分析的基础标准:“分析的车轮示意图”实际上,上述定义的每个词都有其重要性。在下面的“车轮状”示意图中,我对分析的这个定义进行了详细的阐释,以明确良好分析的标准。 让我们进一步解读这些标准:

我们每个人都有天然的优势和劣势。例如,我们中的一些人在清晰地表达他们的论点方面没有问题,但在使他们研究课题环环相扣方面却很费劲;也有人擅长提供丰富的解读,但却不太能呈现他们是如何得出这些结论的。我们需要做的,首先是了解清楚哪些分析维度是我们的弱点,或者哪些维度是我们经常会忽视的,随后,将我们所意识到的我们的劣势作为优先事项而加以努力。 “车轮状的分析过程示意图”,或许可以作为一个罗盘来指导我们的工作,使其“更有分析性”,而使用这个示意图检测我们研究的关键时刻,是在我们完成第一稿之后。我们可以把车轮中所标注的流程作为一个检查表,把它的不同要素与我们迄今取得的结果进行比较。我们是在提供解读,还是仅仅描述数据中的内容?我们是把我们的分析作为自己的总结来写,还是作为旨在说服听众的论述来写?我们需要在这个车轮状的示意图与我们的分析之间反复检查 This article is also available in English here, and as pdf. Puede leer el artículo en español aquí. |

AuthorAudrey Alejandro Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed