|

Si, como estudiante, alguna vez te han dicho que tu trabajo es “demasiado descriptivo” y que necesitas ser más analítico… Si, como docente, alguna vez le has dicho a tus alumnos que su trabajo es “demasiado descriptivo” y falto de “profundidad analítica”… … ¡este post está escrito pensando en ti!

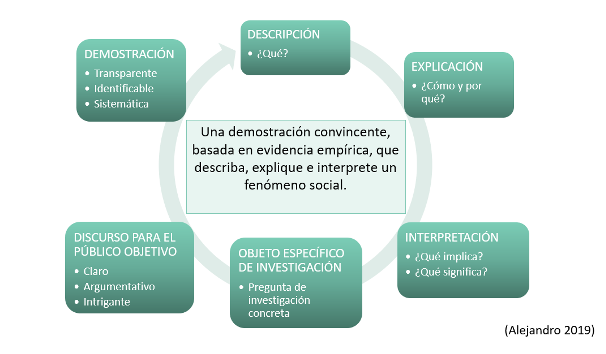

¿Pero entonces qué es el análisis, y qué hace falta para producir un buen análisis ¿Qué significa analizar?El análisis es un proceso de transformación. Los datos y la información en sí no tienen significado, eres tú el que extrae significados a través del proceso del análisis. El análisis es un proceso creativo. Lo que produces por medio del análisis es un nuevo discurso sobre el mundo que nos rodea. Esto a su vez permite a otras personas percibir el mundo de una manera diferente, comprender cosas que desconocían o que no entendían antes de leer tu investigación. ¿Pero cómo funciona? ¿De qué manera conseguimos comprender el mundo a través del análisis? En resumen, se consigue aportando detalle, sintetizando, categorizando, estableciendo patrones y relaciones que ayuden a otras personas a percibir dichos patrones y relaciones y por tanto a comprender el mundo de un modo diferente. El trabajo de los astrónomos y demás personas dedicadas a identificar constelaciones es una buena metáfora para expresar lo que significa el análisis. El universo está lleno de estrellas. Sin embargo, en un origen algunas personas comenzaron a identificar figuras en el cielo, les dieron nombres e incluso crearon historias en torno a las figuras formadas. Esta manera de comprender el universo fue heredada de generación en generación, enseñada y recogida en libros. A su vez, las personas que aprenden esas constelaciones se acostumbran a verlas de manera intuitiva cada vez que miran al cielo. Éstas son un par de definiciones de análisis extraídas de libros de texto sobre metodología: «De manera literal, “desmontar” algo complejo en partes más pequeñas y explicar el todo en función de las propiedades e interrelaciones de las partes» (Robson 2011: 412, traducción del original en inglés). «El proceso de ordenar los datos, organizándolos en función de patrones, categorías y unidades descriptivas, y de buscar interrelaciones entre ellos. La “interpretación” implica atribuir significado y valor al análisis, explicando dichos patrones, categorías y relaciones […]» (Brewer 2000: 105, traducción del original en inglés). Ambas definiciones destacan el doble proceso en que consiste el trabajo de análisis. Por un lado, descomponer y simplificar un fenómeno complejo; por otro, seleccionar determinados elementos para construir patrones que produzcan una manera original y sintética de interpretar el mundo. En la práctica, la transcripción de una hora de entrevista puede ocupar hasta 40 páginas. Por tanto, digamos que la transcripción de 10 entrevistas ocupa unas 400 páginas. Para analizarlas, es necesario dividir todo ese material en segmentos manejables, y a partir de aquí centrarse en ciertos elementos a costa de ignorar otros, para así poder encontrar cuáles son los resultados más interesantes que se puede producir a partir de esos datos. Entonces… ¿todo vale? A partir de lo que hemos hablado hasta ahora surge una pregunta: ¿es aceptable en las ciencias sociales crear cualquier significado o discurso a partir de nuestros datos? Si bien el análisis es un proceso creativo, ¿significa eso que todo vale? La respuesta es ¡NO! Es importante en ciencias sociales comprender que el significado no es inherente a los datos, sino que es el resultado de un proceso que implica tanto el material empírico como la labor del investigador o investigadora. Pero eso no implica que cualquier tipo de discurso que puedas crear a partir de esos datos sea relevante en términos científicos. Establecer unos criterios explícitos sobre qué es lo que necesitamos hacer para producir un buen análisis es útil para no perder de vista el objetivo de nuestro análisis. En resumen, el objetivo del análisis es producir una demostración convincente, basada en evidencia empírica, que describa, explique e interprete un fenómeno social. Criterios de análisis 101: la “rueda del análisis”Cada palabra en la definición que he aportado tiene su importancia. En el esquema de “rueda” que presento a continuación, desarrollo en detalle las diferentes partes de esta definición para clarificar los criterios para un buen análisis: Veamos lo que significan estos criterios en más detalle:

Todos tenemos nuestras fortalezas y nuestras debilidades. Por ejemplo, algunos tienen facilidad para expresar sus argumentos con claridad pero les cuesta acotar su tema de investigación. Otros tienen habilidad a la hora de desarrollar interpretaciones interesantes, pero no a la hora de demostrar cómo han alcanzado dichas conclusiones. Es importante adquirir consciencia de cuáles de las dimensiones del análisis son nuestras fortalezas y cuáles nuestras debilidades, o cuáles tendemos a descuidar y por tanto requieren que las trabajemos con mayor atención. La “rueda del análisis” puede ser utilizada como un compás para guiar nuestro trabajo y hacerlo “más analítico.” Otro momento perfecto para usarla es cuando hayas acabado tu primer borrador: usa la rueda como una checklist, comparando sus diferentes elementos con lo que has conseguido hasta el momento. ¿Estás construyendo una interpretación, o simplemente describiendo lo que arrojan los datos? ¿Has escrito tu análisis como un discurso pensado para convencer a un público, o más bien como un resumen para ti mismo? A medida que avances en tu análisis, ves contrastando la rueda con tu trabajo hasta que lo desarrolles lo suficiente como para cubrir todas las dimensiones. This article is also available in English and Chinese.

0 Comments

Designing research implies a lot of steps, and when comes the time to submit our project and we are stressed out and tired, one can easily find themselves overwhelmed with the number of things there is left to check before pressing the submission button. Below I compiled a list of questions I encourage you to go through to self-assess the research design dimensions of your manuscript and rectify trajectory if necessary. Obviously, no such checklist can be exhaustive nor can it match the specific requirements of the many types of format of research projects out there. This is a starting point with some common essentials and it is your responsibility to identify the more specific questions to cover all angles of your research design. Good luck on pushing your project over the finishing line 😎 🏁 😎 🏁 Introduction

Research question

Analytical framework

Research Design

Method of Data Collection

Method of data Analysis

Results

Reflexivity, Ethics, and Limits of your project

|

AuthorAudrey Alejandro Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed