|

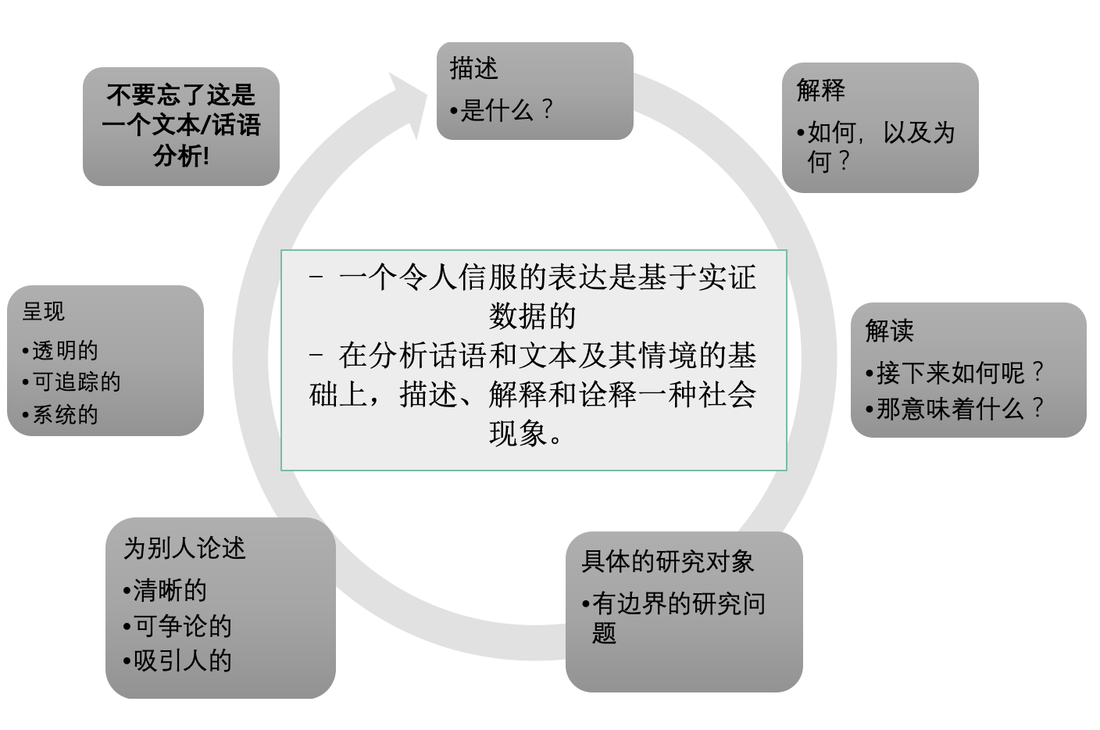

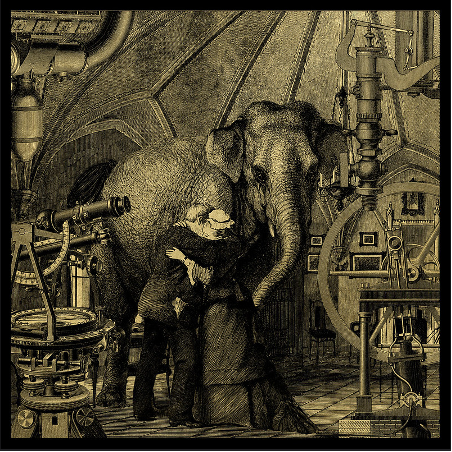

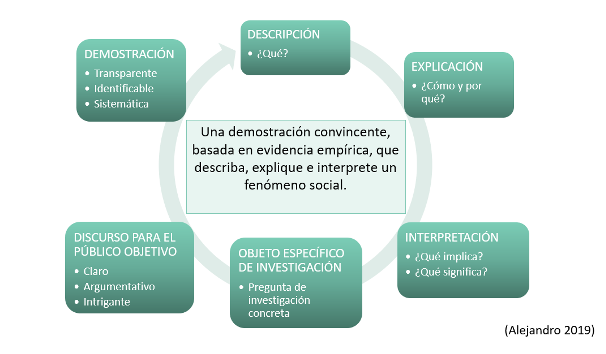

如果作为学生,你曾被告知:你的研究“描述性太强”,你需要“更具分析性”; 如果作为一名教师,你曾告诉你的学生:你们的作业“描述性太强”,缺乏“分析深度”。 那么,你应该来读读这篇文章。  seriykotik1970-房间里的大象 seriykotik1970-房间里的大象 事实上,尽管我们普遍鼓励让作业和研究论文“更具分析性”,但老师可能从未让学生知道,什么是好的分析标准。分析,可以说是社会科学殿堂中的一头大象,包括所有的那些带有“数据分析”字眼的相关课程——例如我所开设的“话语分析”。 那么,什么是分析,以及要怎样才能实现良好的分析工作? 什么是分析?分析是一个转化的过程:原始数据和信息本身并不具有意义,是我们通过分析的过程赋予其意义。 分析也是一个创造的过程:我们通过分析所创造的是,关于世界的新话语,它帮助人们以不同的方式感知世界,从而理解他们在阅读我们的研究之前,不知道或不理解的事情。 但分析是如何生效的呢?分析又是如何使世界变得有意义的呢?笼统地说:分析,通过聚焦、整理、命名以及建立范式与关系,来帮助其他人建立对这些范式与关系的感知,从而以不同方式理解世界。 有一个关于分析的比喻很好,那就是天文学家和其他观星爱好者识别星座的工作。天空布满了星星,但是尽管如此,有些人还是在天空中画出了图案,给这些图案命名,甚至围绕着这样形成的形状创造了一系列故事。这种感知天空的方式代代相传,被人们传授并写在书上,了解过这些知识的人在看星星的时候,都会不自觉地注意到星座。 以下,是来自方法论专著中的两个关于分析的定义: “从字面上看,分析是将复杂的东西‘分解’成较小的部分,并以这些较小的部分的属性和它们之间的关系,来解释整体” (Robson 2011: 412) “分析是给数据带来秩序的过程,它将已存在的东西组织成模式、类别和描述性单元,并寻找它们之间的关系;‘解读(interpretation)’涉及在分析中赋予意义和重要性,从而解释模式、类别和关系...”(Brewer 2000: 105) 这些定义,突出了分析工作中的双重过程。一方面,分析工作是对复杂混乱的现象进行分解和简化;另一方面,分析工作会在选定的元素之间建立模式,以产生一种解释世界的新的混合思路。 在研究的实际操作中,一个小时的访谈,转录记录可能会多达40页纸,而10个访谈的转录记录,就相当于400页纸。我们需要将我们的材料分解成可管理的部分,并专注于某些元素而放弃其他元素,以便我们能识别出隐藏在这些数据中的最有趣的知识。 这是否意味着万事俱备? 作为社会科学家,从我们的数据中创造任何意义和话语是可以的吗?我说过,分析是一个创造性的过程,但这是否意味着可以创造一切? 答案当然是否定的。意义不是原始数据所固有的,而是研究者在培育经验材料的过程中,与其共谋的结果;因此,这一观点并不意味着从社会科学的目的出发,我们能从数据中随意创造任何话语。 针对我们需要怎么做才能实现良好的分析的问题,我们需要制定一些明确的标准,才能帮助我们确保我们的分析目标处于正轨。总结一下就是说:分析的目的是在基于经验数据的基础上,产生一个令人信服的证明,以描述、解释和解读一个社会现象 分析的基础标准:“分析的车轮示意图”实际上,上述定义的每个词都有其重要性。在下面的“车轮状”示意图中,我对分析的这个定义进行了详细的阐释,以明确良好分析的标准。 让我们进一步解读这些标准:

我们每个人都有天然的优势和劣势。例如,我们中的一些人在清晰地表达他们的论点方面没有问题,但在使他们研究课题环环相扣方面却很费劲;也有人擅长提供丰富的解读,但却不太能呈现他们是如何得出这些结论的。我们需要做的,首先是了解清楚哪些分析维度是我们的弱点,或者哪些维度是我们经常会忽视的,随后,将我们所意识到的我们的劣势作为优先事项而加以努力。 “车轮状的分析过程示意图”,或许可以作为一个罗盘来指导我们的工作,使其“更有分析性”,而使用这个示意图检测我们研究的关键时刻,是在我们完成第一稿之后。我们可以把车轮中所标注的流程作为一个检查表,把它的不同要素与我们迄今取得的结果进行比较。我们是在提供解读,还是仅仅描述数据中的内容?我们是把我们的分析作为自己的总结来写,还是作为旨在说服听众的论述来写?我们需要在这个车轮状的示意图与我们的分析之间反复检查 This article is also available in English here, and as pdf. Puede leer el artículo en español aquí.

0 Comments

Si, como estudiante, alguna vez te han dicho que tu trabajo es “demasiado descriptivo” y que necesitas ser más analítico… Si, como docente, alguna vez le has dicho a tus alumnos que su trabajo es “demasiado descriptivo” y falto de “profundidad analítica”… … ¡este post está escrito pensando en ti!

¿Pero entonces qué es el análisis, y qué hace falta para producir un buen análisis ¿Qué significa analizar?El análisis es un proceso de transformación. Los datos y la información en sí no tienen significado, eres tú el que extrae significados a través del proceso del análisis. El análisis es un proceso creativo. Lo que produces por medio del análisis es un nuevo discurso sobre el mundo que nos rodea. Esto a su vez permite a otras personas percibir el mundo de una manera diferente, comprender cosas que desconocían o que no entendían antes de leer tu investigación. ¿Pero cómo funciona? ¿De qué manera conseguimos comprender el mundo a través del análisis? En resumen, se consigue aportando detalle, sintetizando, categorizando, estableciendo patrones y relaciones que ayuden a otras personas a percibir dichos patrones y relaciones y por tanto a comprender el mundo de un modo diferente. El trabajo de los astrónomos y demás personas dedicadas a identificar constelaciones es una buena metáfora para expresar lo que significa el análisis. El universo está lleno de estrellas. Sin embargo, en un origen algunas personas comenzaron a identificar figuras en el cielo, les dieron nombres e incluso crearon historias en torno a las figuras formadas. Esta manera de comprender el universo fue heredada de generación en generación, enseñada y recogida en libros. A su vez, las personas que aprenden esas constelaciones se acostumbran a verlas de manera intuitiva cada vez que miran al cielo. Éstas son un par de definiciones de análisis extraídas de libros de texto sobre metodología: «De manera literal, “desmontar” algo complejo en partes más pequeñas y explicar el todo en función de las propiedades e interrelaciones de las partes» (Robson 2011: 412, traducción del original en inglés). «El proceso de ordenar los datos, organizándolos en función de patrones, categorías y unidades descriptivas, y de buscar interrelaciones entre ellos. La “interpretación” implica atribuir significado y valor al análisis, explicando dichos patrones, categorías y relaciones […]» (Brewer 2000: 105, traducción del original en inglés). Ambas definiciones destacan el doble proceso en que consiste el trabajo de análisis. Por un lado, descomponer y simplificar un fenómeno complejo; por otro, seleccionar determinados elementos para construir patrones que produzcan una manera original y sintética de interpretar el mundo. En la práctica, la transcripción de una hora de entrevista puede ocupar hasta 40 páginas. Por tanto, digamos que la transcripción de 10 entrevistas ocupa unas 400 páginas. Para analizarlas, es necesario dividir todo ese material en segmentos manejables, y a partir de aquí centrarse en ciertos elementos a costa de ignorar otros, para así poder encontrar cuáles son los resultados más interesantes que se puede producir a partir de esos datos. Entonces… ¿todo vale? A partir de lo que hemos hablado hasta ahora surge una pregunta: ¿es aceptable en las ciencias sociales crear cualquier significado o discurso a partir de nuestros datos? Si bien el análisis es un proceso creativo, ¿significa eso que todo vale? La respuesta es ¡NO! Es importante en ciencias sociales comprender que el significado no es inherente a los datos, sino que es el resultado de un proceso que implica tanto el material empírico como la labor del investigador o investigadora. Pero eso no implica que cualquier tipo de discurso que puedas crear a partir de esos datos sea relevante en términos científicos. Establecer unos criterios explícitos sobre qué es lo que necesitamos hacer para producir un buen análisis es útil para no perder de vista el objetivo de nuestro análisis. En resumen, el objetivo del análisis es producir una demostración convincente, basada en evidencia empírica, que describa, explique e interprete un fenómeno social. Criterios de análisis 101: la “rueda del análisis”Cada palabra en la definición que he aportado tiene su importancia. En el esquema de “rueda” que presento a continuación, desarrollo en detalle las diferentes partes de esta definición para clarificar los criterios para un buen análisis: Veamos lo que significan estos criterios en más detalle:

Todos tenemos nuestras fortalezas y nuestras debilidades. Por ejemplo, algunos tienen facilidad para expresar sus argumentos con claridad pero les cuesta acotar su tema de investigación. Otros tienen habilidad a la hora de desarrollar interpretaciones interesantes, pero no a la hora de demostrar cómo han alcanzado dichas conclusiones. Es importante adquirir consciencia de cuáles de las dimensiones del análisis son nuestras fortalezas y cuáles nuestras debilidades, o cuáles tendemos a descuidar y por tanto requieren que las trabajemos con mayor atención. La “rueda del análisis” puede ser utilizada como un compás para guiar nuestro trabajo y hacerlo “más analítico.” Otro momento perfecto para usarla es cuando hayas acabado tu primer borrador: usa la rueda como una checklist, comparando sus diferentes elementos con lo que has conseguido hasta el momento. ¿Estás construyendo una interpretación, o simplemente describiendo lo que arrojan los datos? ¿Has escrito tu análisis como un discurso pensado para convencer a un público, o más bien como un resumen para ti mismo? A medida que avances en tu análisis, ves contrastando la rueda con tu trabajo hasta que lo desarrolles lo suficiente como para cubrir todas las dimensiones. This article is also available in English and Chinese. |

AuthorAudrey Alejandro Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed